— ON THE SUBJECT

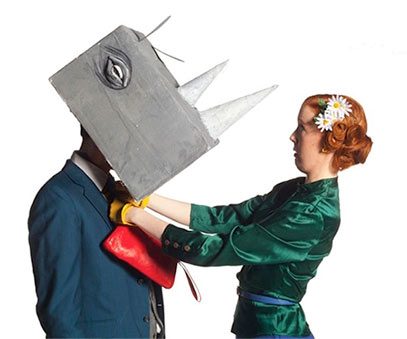

Matt Reznik plays Berenger in Theatre at UBC's production of Rhinoceros. Photo credit: Tim Matheson

RHINOCEROS

What do you do when everyone around you is turning into a rhinoceros?

Eugène Ionesco’s absurdist masterpiece follows a tragic everyman called Berenger, who must navigate the chaos in his small French village as the townsfolk are transformed into stampeding pachyderms. As bipeds become an ever-smaller minority, what will it take for him to stand up to the increasing menace of rhinocerisation? This satirical comedy is an insightful critique of mindless conformity that still resonates today.

“Still astonishing after more than 40 years… “ - New York Times

Eugène Ionesco was one of the most important French playwrights of the 20th century and a leading character of the “absurdist theatre.” In his drama Ionesco focuses on the question of human existence as well as the trivia of everyday life. His most renowned play is Rhinoceros (1959), in which totalitarianism is depicted as a disease that turns human beings into savage rhinoceroses. The play was based on Ionesco’s own experiences in Romania, which inspired him to oppose conformism and act against totalitarianism. Other plays include The Bald Soprano, The Chairs and The Lesson. He was elected to the Académie Française in 1970.

MFA Directing student Chelsea Haberlin is Co-Artistic Director and General Manager of ITSAZOO Productions, a company she co-founded in 2004 and with whom she has many credits. She is a graduate of the University of Victoria with a degree in Theatre and specialization in Applied Theatre and Directing. Credits at UBC include Mark Ravenhill’s Faust is Dead. Favorite ITSAZOO credits include Mojo, Stay Away From My Boat @$$hole, Chairs, Robin Hood, The Road to Canterbury, Five Red Balloons, Grimm Tales, Casualties of, Death of a Clown, Alice in Wonderland and The Zoo Story. More: http://www.itsazoo.org/

Rhinoceros features a riotous herd of 22 actors, including UBC BFA Acting students Georgia Beaty, Morgan Churla, Lara Deglan, Alen Domiguez, Joel Garner, Sarah Harrison, Luke Johnson, Alexander Keurvorst, Kenton Klassen, Kat McLaughlin, Daniel Meron, Nick Preston, Matt Reznek, Courtney Shields and Naomi Vogt. The creative team includes MFA Design students Matthew Norman (Set & Lighting) and Won Kyoon Han (Sound), BFA Design student Christina Dao (Costumes) and BFA Production student Jayda Paige Novak.

Themes, Motifs, and Symbols

Themes

Will and Responsibility

The transformation of Berenger from an apathetic, alcoholic, and ennui- ridden man into the savior of humanity constitutes the major theme of Rhinoceros, and the major existential struggle: one must commit oneself to a significant cause in order to give life meaning.

Jean continually exhorts Berenger to exercise more will-power and not surrender to life's pressures, and other characters, such as Dudard, seem to do just that as they control their own destinies.

Berenger does not have great conventional will-power, as demonstrated by his frequent recourse to alcohol and his tendency to dream (both daydreams and nightmares). However, he maintains a steadfast, latent sense of responsibility after Act One, often feeling guilty for the various rhinoceros-metamorphoses around him—in a sense, his initial apathy was the cause, helping promote a climate of indifference and irresponsibility.

...Berenger practices the most selfless kind of love —

unconditional love for all humanity

He shows early on that he at least cares about Daisy, the only evidence in the play, other than Mrs. Boeuf's devotion to Mr. Boeuf, of sincere love for another human. By Act Three, his powerful guilt and sense of responsibility indicates that Berenger practices the most selfless kind of love—unconditional love for all humanity, whereby he is concerned for the welfare even of those who have scorned him. This all-encompassing love is what gives his life meaning.

...will is a means to metamorphose into

Nietzsche's "super-man,"

a powerful being beyond human morality

The supposedly strong characters, like Jean, fail the ultimate test of will- power, the rhino-epidemic, and their crumbling wills are foreshadowed by their subtler evasions of responsibility—Daisy, for instance, wants to live a guiltless life. Their idea of will borrows from Friedrich Nietzsche's concept of "the will to power." For them, will is a means to metamorphose into Nietzsche's "super-man," a powerful being beyond human morality.

The savagery of the rhinos, and Jean's transformation and statements in Act Two, exemplify this desire for power. He becomes violent, claims humanism is dead, and tries to trample Berenger. The play's final irony is that Berenger becomes the true super-man, gathering his resources of will, built on a foundation of love for his fellow man, to take responsibility for humanity.

Logic and Absurdity

Rhinoceros exposes the limitations of logic, and absurdity reigns as the dominating force in the universe. Self-proclaimed rational characters, such as the Logician, Botard, and Jean, either flounder in their proofs (the Logician, especially) or ridiculously rationalize their incorrect presumptions—consider Botard's accusation of a conspiracy in Act Two.

...if one were to read about

the rhinoceros events in a newspaper, away from the action,

one could be rational and detached,

but in the midst of things

one can't help getting involved

The Logician's attempts to uncover how many rhinoceroses there were in the first act, and what breeds they were, results only in re-posing the original question. In Act One, Berenger calls Jean's ideas "nonsense," and this word resonates throughout Rhinoceros. The world is nonsensical, absurd, and defies the extent of logic. As Berenger says, if one were to read about the rhinoceros events in a newspaper, away from the action, one could be rational and detached, but in the midst of things one can't help getting involved.

Recognizing the world as absurd, Ionesco suggests,

is the first step in cobbling together a meaningful life

The balance between detached distance and intimate confusion divides the supposedly logical characters from Berenger. They maintain their logical distance until confronted with a real problem, when their logic implodes. Berenger concedes absurdity from the outset—"life is a dream," he says, alluding to the inexplicable randomness around him—and this enables him to understand the absurdity of the metamorphoses better, even though he never arrives at a logical "solution." Recognizing the world as absurd, Ionesco suggests, is the first step in cobbling together a meaningful life.

Eugene Ionesco

Fascism

The "epidemic" of the rhinoceroses serves as a convenient allegory for the mass uprising of Nazism and fascism before and during World War II. Ionesco's main reason for writing Rhinoceros is not simply to criticize the horrors of Nazis, but to explore the mentality of those who so easily succumbed to Nazism. A universal consciousness that subverts individual free thought and will defines this mentality; in other words, people get rolled up in the snowball of general opinion around them, and they start thinking what others are thinking.

Ionesco's main reason for writing Rhinoceros

is not simply to criticize the horrors of Nazis,

but to explore the mentality of those

who so easily succumbed to Nazism

In the play, people repeat ideas others have said earlier, or simultaneously say the same things. Once other people, especially authority figures, collapse in the play, the remaining humans find it even easier to justify why the metamorphoses are desirable.

The rhinos become more beautiful

as the play progresses

Ionesco is careful not to make his play a one-sided critique of the brutality of Nazism. The rhinos become more beautiful as the play progresses until they overshadow the ugliness of humanity, and the audience is forced to recognize that an impressionable individual might have similarly perceived the swelling ranks of Nazis as superior.

Dudard's desire to join the "universal family" of the rhinos points to the notion of the rhinos as an Aryan master race, physically superior to the rest of humanity. Nevertheless, they are still morally repugnant, escalating their violence over the course of the play. Ionesco carefully traces an argument against John Stuart Mill's "harm principle," which states that individual freedom should be preserved so long as it does not harm anyone else. Ionesco demonstrates that passively allowing the rhinos to go on—or, allegorically, turning a blind eye to fascism, as individual citizens and entire countries did in the 1930s—is as harmful as direct violence.

Motifs

Theatre of the Absurd

Ionesco breaks the "fourth wall" of the theater

(and numerous other walls and structures explode in the play)

to make the audience leave the theater

feeling that the absurdity they witnessed

was somehow more real

than a "realistic" play

In the tradition of Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot, Jean-Paul Sartre's No Exit, and Harold Pinter's plays, Ionesco's drama combines abstract philosophical ideas with concrete humor. The various rationalizations that characters come up with to explain their previous errors delight us with their silliness, but they also suggest deeper ideas about logic and responsibility. As many of the plays from the Theatre of the Absurd go, Rhinoceros is conscious of itself as a play, as when Jean suggests Berenger sees one of Ionesco's plays, but more so in the ways that it forces the audience to recognize the production before them as a play and not as a diversion. A production with back-lit rhinoceros heads stakes no claim to the typical drama's attempts to suspend the audience's disbelief, but this is the point: Ionesco breaks the "fourth wall" of the theater (and numerous other walls and structures explode in the play) to make the audience leave the theater feeling that the absurdity they witnessed was somehow more real than a "realistic" play.

Bourgeois Life

Ionesco makes a number of critiques of the emptiness of the bourgeois working world. The root of Berenger's apathy seems to spring from his boring job, and Act Two presents us with the drudgery of his office, its repetitive work, and its shallow relationships built to serve the corporation. Jean recommends that Berenger improve his cultural vocabulary, but Jean's appreciation for the avant- garde theater, for instance, is clearly only a surface interest or he would not succumb so easily to the rhinoceroses. Berenger's reliance upon alcohol is understandable—the ennui of daily life is too great not to escape. In fact, the escapism of alcohol is a trope for the escapism of the metamorphoses; both Berenger and the others feel they regain their lost identities in their respective escapes. The others, then, are similarly oppressed by their jobs (Jean feels it is something one must get used to), though Berenger seems to be the only one who has a deeper awareness of the way bourgeois life crushes his spirit.

Matt Reznik and Georgia Beaty in Theatre at UBC's production of Rhinoceros. Photo credit: Tim Matheson

Symbols

Rhinoceroses

The rhinoceroses are a blunt symbol of man's inherent savage nature but, to Ionesco's credit, the articulation of this idea deploys slowly throughout the play: the first rhino causes no apparent damage; the second one tramples a cat; later ones destroy more property and Jean-as-rhinoceros attacks Berenger. They represent both fascist tyranny and the absurdity of a universe that could produce such metamorphoses. These ideas crystallize into one question: how could humans be this savage, allowing the barbarity of World War II Nazism? Ionesco answers this in a variety of ways. He equates the epidemic of the metamorphoses with the ways the ideals of Nazism can infect the unconscious minds of individuals. Yet the rhinos become more beautiful and humans more ugly by the end of the play. They are beautiful, however, because of their brute strength and power; true beauty, as Berenger demonstrates when he finally decides to fight the rhinos and save humanity, lies in moral strength.